- 1.0Why Is Machinability Worth Serious Study?

- 2.0What Is the Machinability of Metal Materials?

- 3.0How Is Machinability Evaluated?

- 4.0Machinability Classification of Different Materials (Engineering Perspective)

- 5.0Which Material Properties Determine Machinability?

- 6.0How Can Machinability Be Improved in Engineering Practice?

- 7.0Conclusion: Machinability Is a System-Level Engineering Issue

- 8.0FAQ: Common Questions About Metal Machinability

- 8.1Q1: Is machinability equivalent to material hardness?

- 8.2Q2: Why are titanium alloys generally regarded as difficult-to-machine materials?

- 8.3Q3: Is stainless steel always more difficult to machine than carbon steel?

- 8.4Q4: When machinability is poor, is reducing cutting speed the only solution?

- 8.5Q5: How significant is the impact of heat treatment on machinability?

In the field of mechanical manufacturing, machining is everywhere. However, engineers quickly realize in real production that:“Machinable” does not mean “easy to machine.”

With the same machine tool and identical cutting parameters, simply changing the material can lead to completely different cutting forces, tool life, and surface quality. This difference is determined by the material’s machinability.

From an engineering practice perspective, this article systematically introduces the concept of metal machinability, common evaluation methods, major influencing factors, and proven strategies for improvement in real production environments.

1.0Why Is Machinability Worth Serious Study?

Machining remains one of the most widely used metal forming methods in modern manufacturing. Yet different materials behave very differently during cutting.

1.1Example performance differences in cutting:

- Aluminum alloys, copper alloys: Light cutting, low cutting forces, high efficiency;

- Alloy steels, stainless steels, titanium alloys, nickel-based superalloys: High cutting forces, concentrated heat, rapid tool wear, often accompanied by edge chipping and vibration issues.

1.2Consequences of inadequate understanding of machinability:

- Significantly reduced tool life;

- Persistently low machining efficiency;

- Unstable surface quality;

- Repeated trial-and-error in process parameter optimization.

Therefore, understanding the essence of machinability and applying targeted strategies is fundamental to improving efficiency, controlling costs, and ensuring stable machining performance.

2.0What Is the Machinability of Metal Materials?

The machinability of a metal material refers to the degree of difficulty with which it can be machined under specified cutting conditions and a defined tool life requirement.

From an engineering standpoint, a material with “good machinability” typically exhibits:

- Higher allowable cutting speeds under the same tool life conditions;

- Lower cutting forces and cutting temperatures, with slower tool wear;

- Stable surface quality, with chips that break easily and can be evacuated in a controlled manner.

Conversely, if a material results in short tool life, high cutting resistance, poor surface finish, or difficult chip control, it is generally considered to have poor machinability.

It should be emphasized that machinability is a relative concept, not an inherent judgment of whether a material is “good” or “bad.”

3.0How Is Machinability Evaluated?

3.1Common Engineering Evaluation Metrics

In practical engineering applications, machinability is usually assessed through a combination of indicators, including:

- Tool life;

- Allowable cutting speed;

- Cutting force;

- Cutting temperature;

- Machined surface quality;

- Chip morphology.

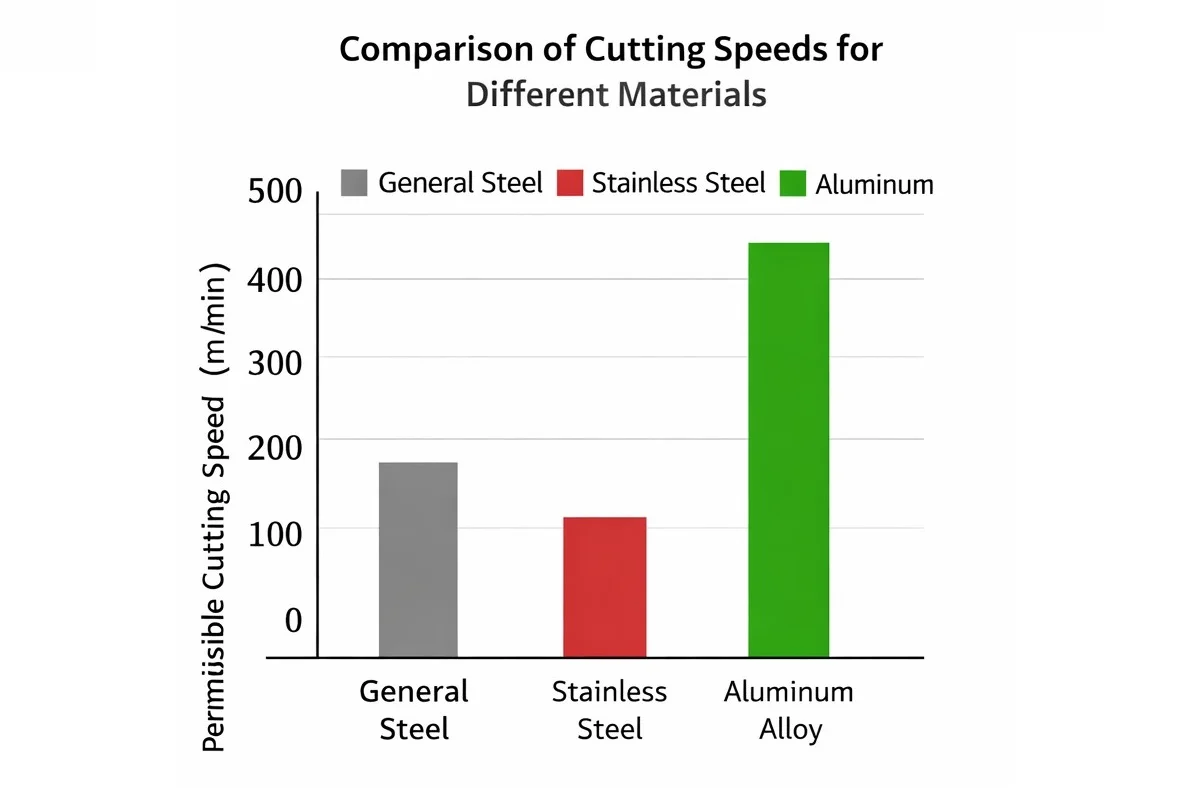

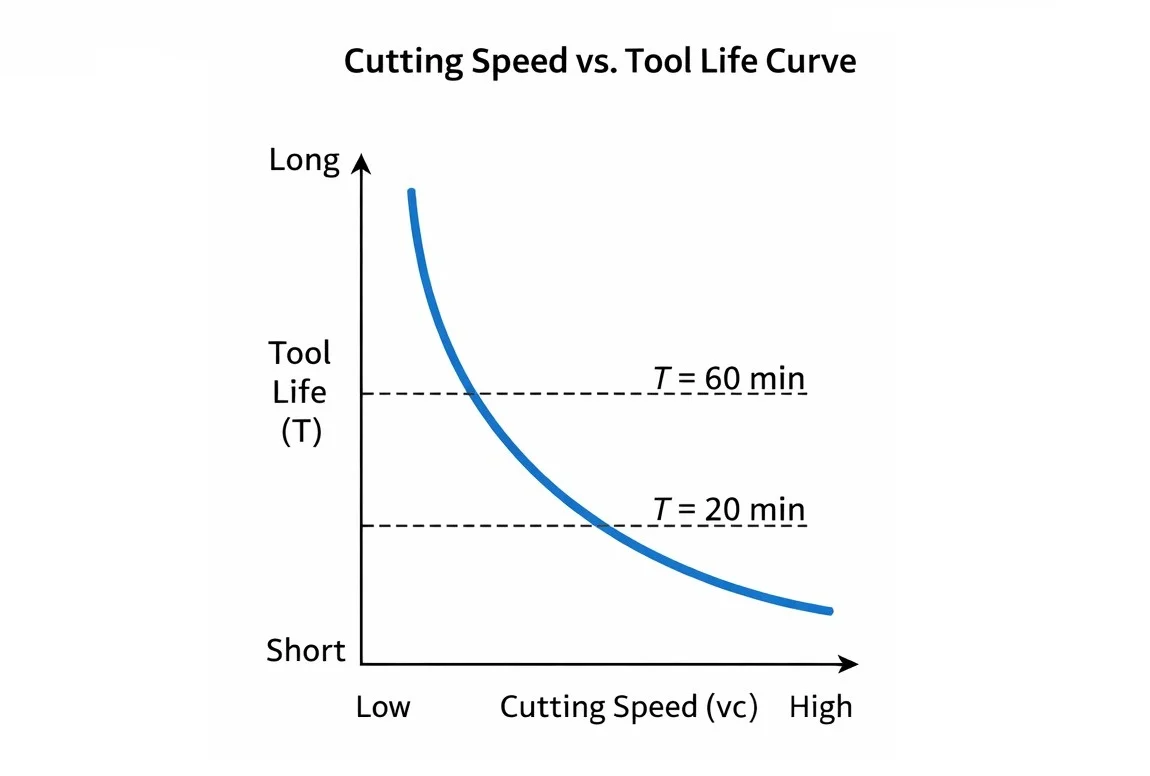

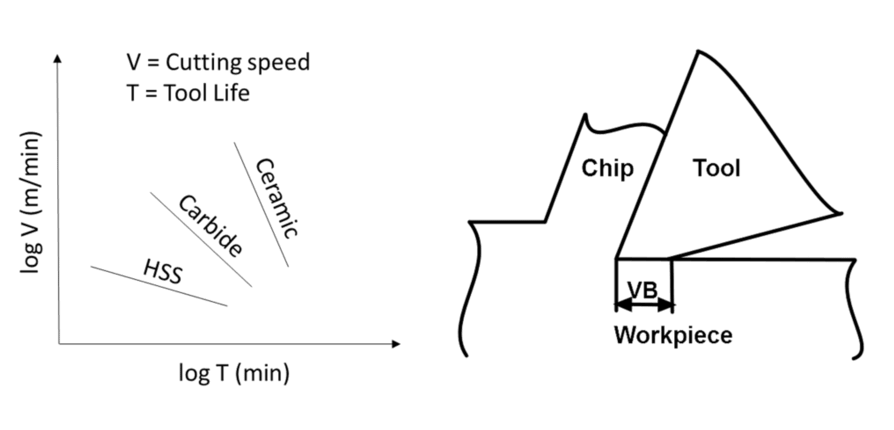

Among these, the allowable cutting speed at a specified tool life is the most commonly used and most engineering-relevant quantitative indicator:

- General metal materials: Cutting speed at tool life T = 60 min (vc₆₀) is used as the reference;

- Difficult-to-machine materials: Cutting speed at tool life T = 20 min (vc₂₀) is often adopted.

3.2Relative Machinability Index Kr

To facilitate comparison between different materials, the relative machinability index Kr is widely used in engineering practice:Kr = Cutting speed of the material at T = 60 min / Cutting speed of AISI 1045 steel at T = 60 min

Here, AISI 1045 steel (170–229 HBS) serves as the reference material.

- Kr > 1: Machinability is better than 1045 steel;

- Kr < 1: Machinability is worse than 1045 steel.

This index is particularly useful for material selection and preliminary process planning in engineering applications.

4.0Machinability Classification of Different Materials (Engineering Perspective)

Based on the relative machinability index Kr, materials are commonly classified in engineering practice into multiple levels ranging from “easy-to-machine” to “extremely difficult-to-machine.” This classification is widely used for rapid assessment of machining difficulty during material selection and process planning.

A widely accepted rule is as follows:As material strength, plasticity, or high-temperature performance increases, machinability tends to decrease significantly.

This explains why titanium alloys and nickel-based superalloys exhibit excellent mechanical and thermal properties, yet are extremely challenging to machine.

5.0Which Material Properties Determine Machinability?

5.1Hardness and Strength

As hardness and strength increase, shear resistance during cutting rises accordingly, resulting in higher cutting forces and cutting temperatures and accelerated tool wear.

Engineering experience shows that materials with moderate hardness and uniform microstructure are more favorable for stable machining.

5.2Plasticity and Toughness

- Excessive plasticity: severe plastic deformation occurs during cutting, expanding the tool–chip contact area, increasing friction, and promoting built-up edge formation;

- Excessive toughness: cutting energy consumption increases and chip breaking becomes difficult.

Both conditions significantly reduce machinability.

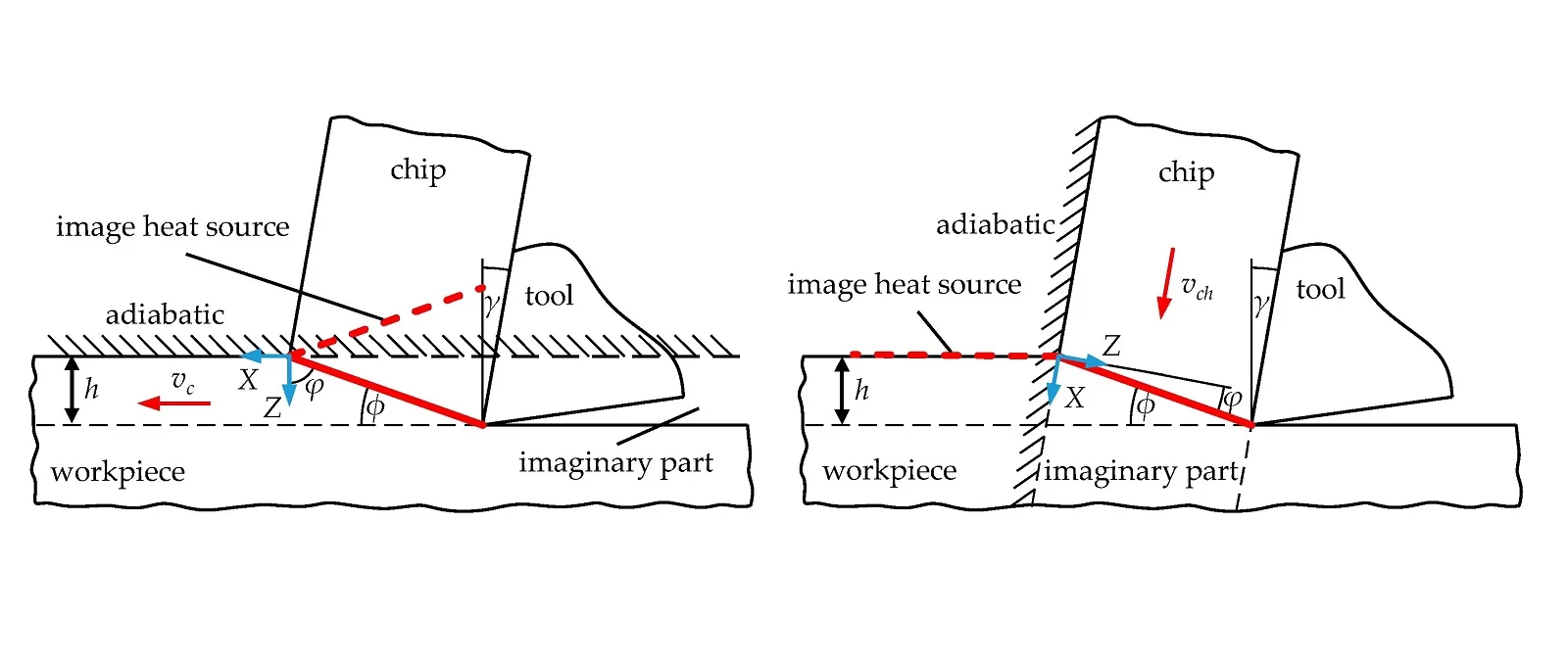

5.3Thermal Conductivity

Materials with good thermal conductivity can dissipate cutting heat efficiently through the chip and workpiece, reducing cutting zone temperature and mitigating thermal tool wear.

Materials with poor thermal conductivity, such as titanium alloys, tend to concentrate heat near the cutting edge, accelerating tool failure.

5.4Elastic Modulus

- Excessively high elastic modulus: higher cutting resistance during material removal;

- Excessively low elastic modulus: pronounced elastic recovery after cutting, increasing friction between the flank face and the machined surface.

Both cases are unfavorable for machining stability.

6.0How Can Machinability Be Improved in Engineering Practice?

6.1Improving Machinability Through Heat Treatment

Proper heat treatment can significantly enhance machining performance by modifying the microstructure:

- Low-carbon steels: normalizing to refine grains and reduce excessive plasticity;

- High-carbon steels: spheroidizing annealing to reduce hardness and improve chip breaking;

- Cast iron: annealing prior to machining to relieve internal stresses and reduce surface hardness.

6.2Improving Machinability Through Chemical Composition Optimization

In mass production, machinability is often improved through alloy design:

- Adding sulfur, phosphorus, lead, or calcium to steel can reduce cutting resistance and enhance chip breakability;

- Optimizing alloy composition in non-ferrous metals can refine grain structure and improve machining stability.

6.3Machining Optimization Strategies for Typical Difficult-to-Machine Materials

High-Strength and Ultra-High-Strength Materials

For these materials, cutting forces are typically 20%–30% higher than those of AISI 1045 steel, with elevated cutting temperatures and rapid tool wear.

Engineering strategies include:

- Selecting cutting tool materials with excellent heat resistance and wear resistance;

- Reducing rake angle or adopting negative rake angles and increasing tool nose radius to improve edge strength;

- Performing rough machining in annealed or normalized condition whenever possible;

- Controlling cutting speed reasonably rather than excessively pursuing high speed.

High-Plasticity, Low-Hardness Materials

Such materials are prone to adhesion, cold welding, and built-up edge formation, resulting in unstable surface quality.

Effective measures include:

- Using sharp cutting edges to reduce cutting deformation;

- Moderately increasing cutting speed to avoid the built-up edge formation zone;

- Applying appropriate feed rates to improve chip-breaking capability.

7.0Conclusion: Machinability Is a System-Level Engineering Issue

Metal machinability is not determined by a single factor, but by the combined effects of material properties, cutting tool characteristics, and machining parameters.

In engineering practice:

- At the material level: machinability can be improved through heat treatment and chemical composition optimization;

- At the process level: systematic optimization of tools and cutting parameters is required for difficult-to-machine materials.

Only by understanding why a material is difficult to machine can truly effective machining strategies be developed, achieving a balanced optimization of efficiency, quality, and cost.

8.0FAQ: Common Questions About Metal Machinability

8.1Q1: Is machinability equivalent to material hardness?

No. Hardness is only one of the factors influencing machinability and is not a decisive indicator.

In actual machining, plasticity, toughness, thermal conductivity, elastic modulus, as well as friction and chemical affinity between the workpiece material and the cutting tool, all have a significant impact on cutting behavior. For example, titanium alloys do not have particularly high hardness, yet they are still considered difficult-to-machine materials due to poor thermal conductivity and high chemical reactivity.

8.2Q2: Why are titanium alloys generally regarded as difficult-to-machine materials?

The poor machinability of titanium alloys mainly results from the following factors:

- Low thermal conductivity: cutting heat is difficult to dissipate, leading to localized high temperatures at the tool tip;

- High chemical activity: strong tendency to adhere to tool materials, causing adhesion and diffusion wear;

- Pronounced elastic recovery: increased friction on the tool flank face.

These factors act together, making titanium alloys prone to rapid tool wear, edge chipping, and unstable machining conditions.

8.3Q3: Is stainless steel always more difficult to machine than carbon steel?

Not necessarily. The machinability of stainless steel is closely related to its microstructural type:

- Austenitic stainless steels: high plasticity and severe work hardening, resulting in poor machinability;

- Some martensitic stainless steels: under appropriate heat treatment conditions, machinability can approach or be slightly lower than that of medium-carbon steels;

- Free-machining stainless steels: sulfur-containing grades perform well in automatic and high-productivity machining.

Therefore, stainless steel should not be treated as a uniformly difficult-to-machine material.

8.4Q4: When machinability is poor, is reducing cutting speed the only solution?

No. Simply reducing cutting speed often only alleviates symptoms rather than addressing the root cause.

More effective approaches include:

- Selecting more suitable cutting tool materials;

- Optimizing tool geometry: rake angle, cutting edge strength, and tool nose radius;

- Adjusting the combination of cutting parameters;

- Changing the workpiece heat treatment condition when necessary.

In many cases, appropriately increasing cutting speed can actually help reduce built-up edge formation and improve surface finish.

8.5Q5: How significant is the impact of heat treatment on machinability?

The impact is substantial. Through normalizing, annealing, or spheroidizing annealing, heat treatment can:

- Modify the material microstructure;

- Reduce cutting forces;

- Improve chip-breaking behavior;

- Significantly extend tool life.

Reference

https://www.3erp.com/blog/what-is-machinability-and-how-is-it-measured/

https://elitemoldtech.com/what-is-machinability/ https://www.canadianmetalworking.com/canadianmetalworking/article/metalworking/understanding-machinability