- 1.0How High-Frequency Induction Heating Works

- 2.0Key Parameters of High-Frequency Induction Heaters

- 3.0Frequency Range and Heating Depth (Skin Effect)

- 4.0Influence of Magnetic Permeability Variation and the Curie Point

- 5.0Induction Coil Design and Load Matching

- 6.0Operating Conditions and Thermal Management Considerations

- 7.0Typical Industrial Application Scenarios

- 8.0Technical Analysis of Common Operating Issues

- 9.0Conclusion

High-frequency induction heating technology is widely applied in modern industrial manufacturing due to its high efficiency, concentrated energy delivery, non-contact heating, and ease of integration with automated control systems. Typical applications include brazing, heat treatment (quenching and annealing), sealing, through-heating, and small-scale melting.

As a representative form of electromagnetic heating equipment, the technical performance and practical results of a high-frequency induction heater depend directly on a sound understanding and proper application of its operating principle, system configuration, load matching, and process parameters.

1.0How High-Frequency Induction Heating Works

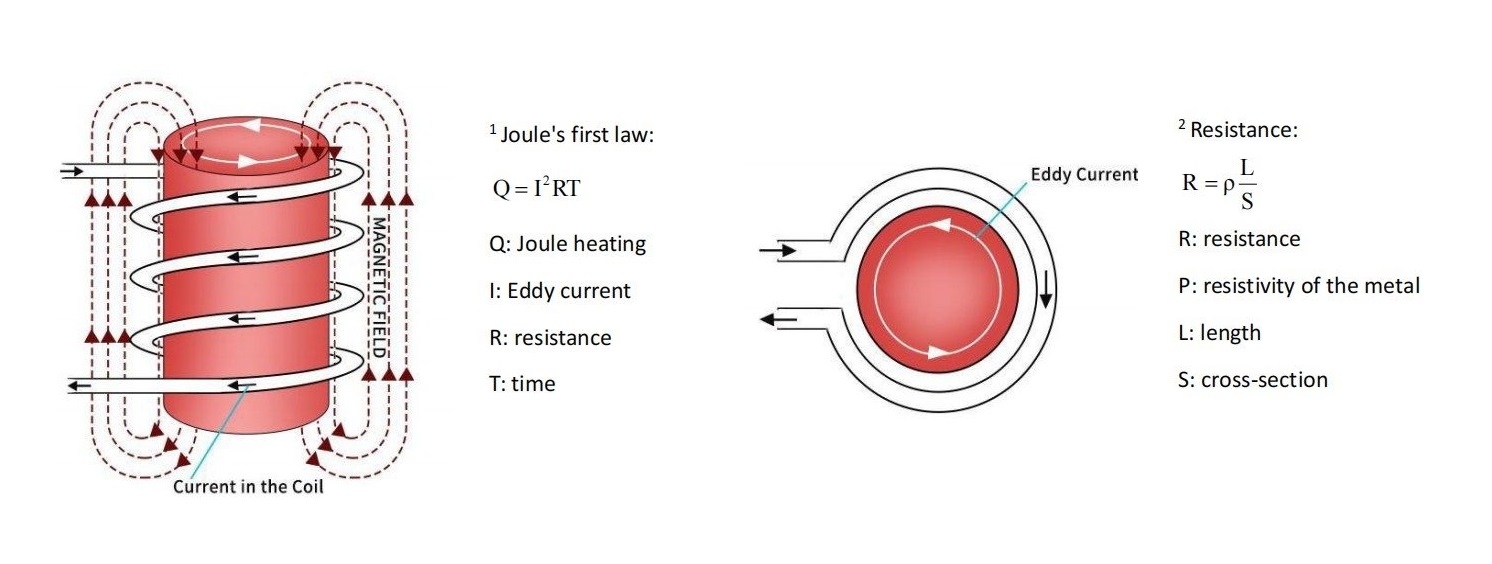

High-frequency induction heating is a heating method based on electromagnetic induction and the Joule heating effect. In essence, it is a non-contact process that converts electrical energy into thermal energy. The basic working mechanism can be summarized in the following stages:

- Generation of an alternating electromagnetic field: When high-frequency alternating current flows through the induction coil, an alternating magnetic field is generated around the coil.

- Induction of eddy currents: When a metal workpiece is placed within the alternating magnetic field, closed-loop currents—known as eddy currents (also referred to as Foucault currents)—are induced inside the material.

- Temperature rise due to the Joule effect: As eddy currents flow within the workpiece, heat is generated due to the electrical resistance of the metal, in accordance with Joule’s law:

Q = I²RT

This internal heat generation enables rapid temperature rise within the workpiece.

During the heating process, the electrical resistivity of most metals increases as temperature rises, which further enhances the Joule heating effect. This is one of the key reasons why induction heating can achieve high heating efficiency within a short time.

In addition, the electrical resistance of a workpiece is related to material resistivity (ρ), effective current path length (L), and cross-sectional area (S), following the relationship:

R = ρL / S

As a result, workpieces with different materials, geometries, and dimensions can exhibit significantly different heating efficiencies under the same induction conditions.

2.0Key Parameters of High-Frequency Induction Heaters

The performance configuration of a high-frequency induction heater typically focuses on output power, operating frequency range, power supply type, and load adaptability. In practical selection, the following factors should be evaluated comprehensively.

2.1Output Power Rating

Output power determines the amount of energy transferred to the workpiece per unit time and is a key parameter affecting heating rate and allowable workpiece size. In general:

- Small-sized, thin-walled workpieces or localized heating applications require relatively low power levels;

- Large workpieces, through-heating processes, or melting applications require significantly higher power output.

2.2Power Supply Conditions

Depending on the application environment, either single-phase or three-phase power supplies can be used. For continuous industrial operation, three-phase power is typically selected to ensure more stable and consistent power output.

2.3Workpiece Material Characteristics

- Magnetic materials exhibit higher magnetic permeability during the initial heating stage, resulting in relatively high induction efficiency;

- Non-magnetic materials, such as copper and aluminum, rely mainly on eddy current heating and usually require more optimized coil design to improve coupling efficiency.

3.0Frequency Range and Heating Depth (Skin Effect)

In high-frequency induction heating, the selection of operating frequency directly determines heating depth and energy distribution. This behavior is primarily governed by the skin effect.

As the alternating current frequency increases, induced currents tend to concentrate near the surface of the metal workpiece, and the effective penetration depth within the material decreases. This leads to the following practical engineering rules:

- Higher frequencies result in shallower heating layers and are better suited for surface heating, surface hardening, and localized heating applications;

- Lower frequencies allow deeper heat penetration, making them more suitable for through-heating or heating thick-walled components.

In practical applications, frequency selection must be evaluated in conjunction with workpiece diameter, wall thickness, and process objectives. For example, in tube end heating operations—such as the heating stage of a Tube End Closing Machine—it is often necessary to achieve rapid temperature rise at the tube end while minimizing heat spread along the tube body. In such cases, relatively higher operating frequencies are preferred to achieve localized energy concentration.

It should be noted that the actual operating frequency of an induction heating system is not a single fixed value. Instead, it is jointly determined by power supply characteristics, coil parameters, and load conditions, with a dynamic matching relationship between frequency and power output.

4.0Influence of Magnetic Permeability Variation and the Curie Point

For ferromagnetic metals such as iron-based materials, the induction heating process is influenced not only by changes in electrical resistivity, but also by significant variations in magnetic permeability with temperature.

At room temperature and within low-to-medium temperature ranges, magnetic materials exhibit high magnetic permeability, allowing the alternating magnetic field to be established more easily within the workpiece. As a result, induction heating efficiency and temperature rise rate are relatively high during the initial heating stage. However, as the material temperature approaches its Curie point, ferromagnetism gradually weakens and ultimately transitions to a paramagnetic state, causing magnetic permeability to drop sharply.

This transition leads to several practical engineering effects:

- Rapid temperature rise during the initial heating stage;

- Reduced heating efficiency and a slower temperature increase as the Curie point is approached;

- Higher input power may be required to maintain the desired heating rate.

In applications involving steel pipes, structural tubes, or tube-end forming processes—including preheating and hot forming stages in Tube End Closing Machines—understanding magnetic permeability variation is critical for maintaining stable heating control. Proper power regulation and optimized coil design help ensure controllable and consistent heating behavior across temperature ranges where magnetic properties change.

5.0Induction Coil Design and Load Matching

The induction coil is the core component of a high-frequency induction heating system. Its geometric configuration, electrical characteristics, and degree of matching with the workpiece directly determine heating efficiency and system stability.

5.1Coil Materials and Structure

- Copper tubing or solid copper conductors are commonly used;

- Adequate cross-sectional area helps reduce coil losses and improve current-carrying capacity;

- Internal cooling channels are typically required to control operating temperature rise.

5.2Coupling Gap Between Coil and Workpiece

- A typical working gap is generally maintained within the range of 5–15 mm;

- Excessive gap reduces magnetic coupling efficiency;

- Insufficient gap increases the risk of short circuits or mechanical contact.

5.3Relationship Between Number of Turns and Operating Behavior

Under otherwise identical conditions:

- Increasing the number of turns lowers the effective operating frequency and increases coil current;

- Reducing the number of turns raises the frequency while decreasing current.

For non-magnetic materials or low-coupling loads, increasing the number of turns is often beneficial for improving heating performance.

5.4Practical Evaluation of Load Matching

During actual operation, current behavior and heating results can be used as empirical indicators:

- High current with slow temperature rise usually indicates insufficient coupling or improper coil dimensions;

- Difficulty increasing current or unstable system operation may indicate excessive load or an overly high number of turns.

By adjusting coil size, number of turns, and workpiece positioning, a more optimal system matching condition can be achieved.

6.0Operating Conditions and Thermal Management Considerations

During high-frequency induction heating, power devices and induction coils operate under high energy density conditions, making effective thermal management essential.

- Cooling media should provide good thermal conductivity and long-term stability;

- The cooling system must ensure continuous and stable flow rate and pressure;

- After prolonged high-power operation, sufficient cooling time should be allowed to reduce thermal stress within the system.

Effective thermal management not only improves operational stability but also significantly extends equipment service life.

7.0Typical Industrial Application Scenarios

High-frequency induction heating technology is widely used across a range of industrial sectors, with different processes imposing distinct requirements on heating methods and parameter control.

| Application Process | Heating Characteristics | Typical Purpose |

| Brazing | Concentrated heating with precise temperature control | Joining dissimilar metals |

| Quenching | Rapid heating followed by controlled cooling | Increasing surface hardness |

| Annealing | Controlled heating and soaking process | Improving ductility and relieving internal stress |

| Through-heating | Uniform heating across the cross section | Heating slender or small-diameter components |

| Sealing | Localized, targeted heating | Structural sealing or component joining |

| Melting | High power density with stable coil operation | Small-batch metal melting |

Actual application performance must be optimized through testing and adjustment based on workpiece material, dimensions, and specific process objectives.

8.0Technical Analysis of Common Operating Issues

During long-term operation or under changing working conditions, induction heating systems may experience reduced efficiency or abnormal behavior. Common causes include:

- Changes in coil geometry or poor electrical contact;

- Variations in load conditions;

- Insufficient cooling capacity triggering thermal protection mechanisms;

- Power supply fluctuations leading to abnormal system response.

To address these issues, systematic analysis and adjustment should be carried out with a focus on load matching, thermal management, and power supply stability.

9.0Conclusion

As a mature and continuously evolving industrial heating technology, the performance of high-frequency induction heaters depends on a comprehensive understanding of electromagnetic principles, coil design, load characteristics, and process control. By properly configuring system parameters and continuously optimizing application strategies, it is possible to achieve high heating quality while maintaining efficient and stable industrial operation.

The information presented here is intended as a general technical reference. Specific applications should be designed and validated according to actual operating conditions and process requirements.

Reference

www.theinductor.com/blog/how-induction-heating-technology-works-and-why-you-should-know/

www.ambrell.com/blog/research-universities-using-induction-heating